Chapter 2

Classic Roller Derby: The Rules

Leading up to their invention official invention, the rules of roller derby went through major changes and revisions as Leo Seltzer tried balancing the integrity of the game with the necessity of putting on a good show for the crowd. Some things worked, like adding the pivot position to the game. Some things didn’t work; an experimental version of roller derby had three teams on the track at once, but that was scrapped when two teams teamed up to bully the third.

Before long a genuine framework for the sport had emerged, and once established the game remained virtually unchanged for over 40 years. The idea of a designated player lapping opponents for points has always been at the core of roller derby, but things like shorter jam length (it was also 2 minutes in the early years, coincidentally), faster and more agile players, and a more, shall we say, liberal interpretation of the rules and lax enforcement of them ultimately made the classic game what it was.

In the end it was still an actual sport, even if the conditions in which it was primarily played didn’t always make it appear that way. If you remove the staged fighting, the pre-determined plays and outcomes, and the over-the-top personalities playing it, all that remains is a set of rules that dictates how roller derby is played.

That’s the thing I’m most interested in taking a closer look at: What are the hows and whys of classic derby rules?

The old game has multiple concepts worth investigating, most of which I’ll get to throughout the course of this series. However, before getting there let’ look back and learn how the game was played in the 1960s and 1970s, the time when roller derby was at its peak in the United States.

Here are the major bullet points on the rules of that era, and a video demonstrating them in action:

Game Parameters

Teams – A team can consist of up to 16 players, but always an equal number of men and women on the same team. (Seven women and seven men on one team of 14, for example.) Though on the same team, men and women were never on the track at the same time during gameplay; it was strictly men vs. men and women vs. women, alternating periods. Men and women “pairs” would wear the same player number on the same team.

Track – The classic game was played exclusively on a banked track with a Masonite skating surface. (It was a bit longer and wider than a modern banked track.) A single start line is marked halfway down one of the straights. Team and penalty benches are located in the infield.

Structure – Games were 96 minutes long, with eight 12-minute periods. (Halftime is after the 4th period.) Women skated in odd-numbered periods (1st, 3rd, etc.) and men in the even-numbered (2nd, 4th, and so on). The team with the highest point total at the end of the game, men and women combined, wins.

Periods – At the start of each half (and overtime) play begins from a standing start when the referee fires the starting gun. In all other periods, the period begins when players are rolling in pack formation and the referee signals for play to begin. The period clock takes precedence over the jam clock, meaning any active jam ends once the period clock expires.

Exception: In the 7th, 8th, and overtime periods, the jam clock takes precedence, allowing a jam to naturally conclude after the expiration of the period.

Jams – Play begins only when the pack is rolling at a comfortable pace and after the referee determines the pack is in a fair starting formation. Pivots must line up at the front of the pack, blockers in the middle, and jammers at the rear. Front pivot position is determined by which team last scored.[1] Both teams must have at least one jammer, one blocker, and one pivot on the track before a jam can begin.

The referee will then sound his whistle to begin play, signaling to the jammers to race through the pack. The 60-second jam begins when a jammer breaks from the pack to become lead jammer, and ends after jam/period time expires or when the lead jammer places hands on hips.

Exception: At the start of each half and in overtime, players begin from from a standing start. Jammers line up on the start line at the front of the pack, with all pivots/blockers behind them. Period and jam time begins when the starting gun is fired. Jammers may immediately break from the pack (as they are already out in front of it) to start scoring.

Lead status is always given to the jammer or pivot most forward on the track. Lead status can change between players (teammates or opponents) when a trailing jammer or pivot overtakes the lead jammer (or pivot). There can be multiple scoring players out on a jam, but there may only be one lead jammer. There must always be one lead jammer on the track at all times once the jam begins.

Players

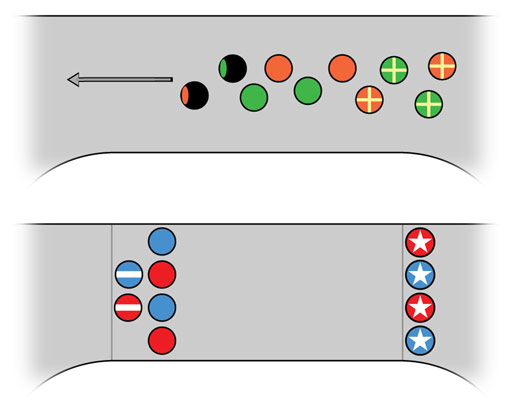

Jammers – Designated with team-colored, cross-striped helmets. They are the offense, with the ability to lap the pack and score points. Once a jammer breaks from the pack and establishes lead position to start the jam, all other position players (jammers/pivots) are also eligible to break from the pack and score. The lead jammer can call off the jam at any time by placing his/her hands on their hips.

Blockers – Designated with solid team-colored helmets. They are the defense, who must prevent the other team from scoring. They cannot score, but can be scored upon. They must remain in the pack at all times.

Pivots – Designated with solid black helmets (regardless of team affiliation). They are a special position that is primarily defense, but can break from the pack and become an offensive player at any point after a jammer breaks from the pack and starts the jam. Pivots are generally regarded as a team’s “playmaker,” the key player who needs to be proficient at both offense and defense.

Helmet Restrictions – A player must be wearing his/her helmet to be the designated position player. A jammer or pivot that loses their helmet may not earn any points until they recover and replace their helmet. Helmets (positions) may never change between players during a jam, only between jams.

The Pack – Blockers must remain in the pack at all times. The pack must move in a counter-clockwise direction at all times (i.e., no stopping or clockwise skating). Pivots initially set the pace of the pack, but once jammers reach scoring position, teams may attempt to maneuver within the pack in an attempt to slow (forward wall) or speed (pullaway) the pack, as tactically necessary.

Blocking

Blockers may make use of any part of their body, except their hands, feet, or skates, to block other players. However, arms may not be used in blocking while fully extended. The point of the elbow may only be swung parallel with the track surface, and never at the head. Teammates may not interlock with their hands or arms in an attempt to form a defensive wall, but may link at the wrists. Referees have the authority to issue penalties for any illegal block or illegal action not explicitly outlined in the rules.

Penalties

Minor penalties – One minute in length. Include illegal blocking, tripping, holding, illegal use of hands, delay of game, and others.

Major penalties – Two minutes in length. Include fighting, unnecessary roughness, insubordination, and unsportsmanlike conduct.

Penalty Enforcement – Penalties are issued during or between jams, and players serving the penalty will report to the penalty bench immediately (but in practice, between jams). A penalized team must skate the duration of the penalty short-handed. All penalties reduce the number of blockers on the track for a team only. (The player is penalized, not the position.) Upon expiration of penalties, players may freely rejoin the pack while gameplay is in progress. Penalties committed near the end of a period carry over into the next period, with men serving women’s penalties and vice versa. Players accumulating eight total penalty minutes in a game are ejected.

Scoring

Any jammer who breaks from the pack is eligible to score points. Any pivot that breaks from the back after the jam begins (after a jammer first breaks from the pack) is also eligible to score. A team may have more than one player out on a scoring attempt simultaneously. A point is earned for every opponent lapped by an active jammer or pivot after the jam has begun. An individual jammer may only score on an opponent once per jam (no multiple scoring passes) but a team can score on a single opponent multiple times if more than one of that team’s jammers/pivots can pass them in the same jam.

A jammer that is fouled by a blocker while attempting to score on them will automatically be awarded a point for their team. Ghost points are awarded to a team’s jammer only if they score on all other opponents on the track during a jam. (That is, a team’s jammer must pass the all the other four players on the track before getting the one box point.)

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Those are the basic rules of the classic roller derby game. Whether the the pioneers of modern roller derby knew it or not, this was the blueprint from which they worked with to make their own rules, rules that are still an ongoing work in progress. Although these rules and the structure of the game served derby well throughout the 20th century, there are probably things in them that would not work in today’s game.

The “anything goes” blocking rules wouldn’t fly, as they would probably be very dangerous. There’s also the fact that the old game had penalties were rarely called for things that would obviously be a foul or penalty in any legitimate sport today, let alone roller derby. A game with more than one active scoring threat per team may be something a legit professional game can someday bring back, but today’s volunteer referees have enough complexity to deal with; one active scoring player per team is fine for now, thanks.

Still, there are some things in the classic rulebook that the modern game would do well to take a closer look at. This is not a suggestion that we copy the old rules into the new rulebook word-for-word; it’s merely a suggestion that the game was setup in the way it was setup for a reason, and if some of the things in it may still hold water today. It would do no harm to at least come to an understanding of why things were done the way they were, in other words.

You may have noticed that there were a couple of bold and underlined passages in the summary of rules. I’ve highlighted these because they may be of use to modern derby’s own efforts to make their versions of the game work better for everyone. There are going to be a few of these throughout this series, so look out for them as we go along.

Of all the concepts of roller derby we’ll be putting under the microscope, though, there’s a very important one that we need to start things off with:

The start.

~ ~ ~ Continue to Chapter 3 ~ ~ ~

[ 1 ] An element of this rule exists today in modern banked track (RDCL) play. The team that scored the most points on the previous jam, gets first pick of inside/outside positioning for their jammer at the jammer start line. (A coin flip determines start position for the first jam of the game.) Return