The second full USA Roller Sports roller derby season has wrapped up, with Washington state pulling off a sweep and Oly taking home two national titles, the men’s (Oly Warriors) and the women’s (Oly Rollers). Thoughts of the event and a complete snapshot of USARS derby, Year Two, will come later in the off-season.

But ahead of that, let’s put on our strategy hats.

All the teams and virtually all the players playing under the USARS banner have very little experience in the faster, more tactical style of roller derby it is trying to develop. Knowing the rules is one thing—at only 10 pages of significance (for now) there is not much to need to know—but applying that knowledge on the track is another thing entirely.

This has been evident during the 2013 USARS tournaments, where teams have been making a lot of strategic mistakes. These mistakes were the major culprit behind some of the more boring sequences of play, including runaway pack situations or instant jam call-offs. These sequences often ended in a 0-0 jam with little action or excitement to show for them.

As with any learning process, these mistakes will pass with practice and game experience. But before one can learn from mistakes, one must know exactly what those mistakes are.

Here are the three most common tactical errors in USARS play over the last two years, from least common to the most.

Mistake #3: Runaway Pivots

In USARS, pivots are granted their traditional ability to break away from the front of the pack and become a jammer, but only after the opposing team has already gotten their jammer out for lead. This ability is most useful when a pivot is controlling the front of the pack, which lets them immediately spring into action should their jammer fail to clear the pack first.

A big chunk of USARS tactics is how the pivots do battle with each other, both at the start of the jam and during the rest of the initial pass sequence. In most circumstances, a pivot will want to be in front of the opposing pivot at all times, to help suck them back into the pack or delay them should they need to break away after the jammer.

Most circumstances. But not all circumstances.

Pivots hell-bent on getting to or staying at the front of the pack during the initial pass hurt a team’s chances of scoring points more than it helps it. This is a mistake made by pivot players new to USARS, and the traditional pivot position in general.

The logic behind this is simple: The scoring player with the best chance to score points on a jam is (generally) the first one reaching the back of the pack on a scoring pass. The first jammer to reach the back of the pack is (usually) the one that gets out of the pack first on the initial pass. The first jammer to get out of the pack is the one that (always) get the most blocking help and assistance from his or her teammates in the pack.

Therefore, a team that works together to make sure their jammer gets out first is well on their way to scoring points. However, a pivot trying too hard to stay ahead of everyone else will wreck this calculus by effectively taking themselves out of play, reducing the blocking power that their jammer might need to do that. A pivot race at the front of the pack can also ramp up the speed of the pack to hopelessly high levels, making it much harder for blockers to stay together or be effective.

Here is a video that shows an example of this happening during a jam. Focus on the white blockers and the white jammer and see how quickly they fall behind due to the white pivot racing the pack forward:

The white pivot ultimately got the position she wanted, the front of the pack. This put her in good position to chase the black jammer out without resistance on the part of the black team.

However, in doing this she left the white jammer in the dust and left the other white blockers vulnerable at the rear of a fast pack. She also put herself out of play ahead of the pack, forcing her to drop back into pack before she could legally activate her jamming abilities. This gave the black jammer a pretty easy scoring pass, picking up two free points.

But more importantly, in playing the jam this way the white pivot was basically guaranteeing her team would not score any points before the initial pass was even completed.

It is important for pivots to stay at the front of the pack in case they are needed to salvage a team’s offensive chances on a jam. However, pivots cannot ignore their defensive responsibilities. Pivots must maintain pack speed control for their team and make sure the opposing jammer does not break through the last line of defense—themselves.

After the initial burst off the line, the white pivot did not take stock of her team’s current situation, which was quickly turning sour: The white team missed their initial blocks, allowing the black team to get by all of them. This let the black team swarm the white pivot, creating the fast pack that doomed the white team from the start.

In this situation, a pivot would be more effective for her team by locking on to the opposing jammer (or any blocker in her immediate path) to slow her down. Doing this would check the speed of the pack and attract the attention of opposing blockers just enough for her teammates to catch up and regain containment, getting them and their jammer back in the play.

Note that in playing defense like this, it is likely that the pivot will get sucked back into the pack, reducing their effectiveness as an offensive option. But as long as the pivot sucks the opposing jammer into the pack with them, that’s just fine. A pivot recycling the jammer to the back and giving the rest of her team a chance to keep containment on the other blockers is exactly what they should be doing as the leader of the pack.

Defensive containment is ultimately the number one priority of a pivot. Players new to the pivot position will need to recognize when to override their offensive desires with the defensive needs of the rest of the team. Although good pivots will occasionally steal away points in tight jammer races, the best pivots must know when to flip the switch from offense to defense by doing whatever necessary to hold back the other team long enough to make sure their jammer is the one leading the way.

Mistake #2: Striking Out on the Grand Slam

As in all forms of roller derby, getting lead jammer status is important. But in a true team game, lead jammer is only half the battle. In USARS, if blockers are not constantly working to contain the opposing blockers within a pack, all those potential points could escape, speed the pack up, and put a scoring opportunity out of reach. If that happens, the lead jammer position is worthless.

In a perfect world, a team will be able to get their jammer out for lead while simultaneously holding back the opposing jammer at the back of the pack, absorbing the opposing pivot from the front of the pack, and containing the opposing blockers from breaking one of its scoring players out on a scoring pass in response. When two teams of unequal strength play each other, the better team will tend to do this a lot, obviously.

But in closer match-ups, getting a jammer out unopposed for a significant amount of time is very difficult given that a team without a jammer in the pack will automatically find themselves at a temporary manpower disadvantage, one the other team will use to get their jammer or pivot out of the pack—usually very quickly.

Trying to play defense against that many opponents almost demands that the pack keep moving as to give blockers more time to work with. A fast pack makes it harder for players to advance their relative position without the aid of a teammate, either with a block to slow opponents ahead or a whip to fling a player past them more quickly.

However, if a fast pack is good for defense, it is simultaneously detrimental for a team’s offensive chances. A fast pack makes it all but impossible for a lead jammer to catch back up to it to score.

Which brings us to USARS strategy mistake number 2: A team with lead jammer tries to contain everyone on the other team for too long, creating a fast pack they risk losing control over, potentially leading to a runaway pack situation and no score.

The longer a team needs to play defense during a jam, the more likely it is that it will make mistakes as fatigue settles in. As the defense breaks down, the pack will start speeding up to compensate. As the pack speeds up, it will also speed away from the lead jammer. If it gets too fast, the lead jammer will be forced to call it off with no hope of catching up to score, even if she had a big distance advantage over the opposing jammer.

A team with lead jammer can be tempted to commit all their defensive resources on the opposing position players, so as to prevent them from getting out of the pack at all. But given the natural 4-on-5 disadvantage it needs to overcome to do this, it is inevitable that the defense will overdo it and let the opposing blockers start gaining forward pack position. Once that happens, the domino effect will take over and the other team will keep pushing to the front, speeding up the pack to the point where it is going just as fast as the jammer trying to catch back up to it.

Which is why in most situations, the best and most realistic chance a team with lead jammer has at scoring safe points in a jam is to let the opposing jammer go well before things get out of hand.This will make sure the blockers containing opponents in the pack are moving fast enough to play effective defense in 2-walls or one-on-one, yet slowly enough for their jammer to be able to come back around on offense and score.

Because if the 4 tries to do too much against the 5…

This is a difficult concept for teams new to USARS. A lot of them have been trained to think that “safe” points are the ones where the jammer, and only the jammer, is kept behind a nice, solid wall of blockers, giving them plenty of time to comfortably pick up a grand slam, or at least a full four-point pass.

However, in USARS, it is (by design) extremely likely that both teams will have a scoring player out on the same scoring pass on every jam, often with little distance between them. For this reason, a team cannot put all their defensive eggs in the initial pass basket and expect to count their points before they hatch. An opposition team has three ways to reply to the lead jammer—a jammer breakout, a pivot breakout, or the blockers gaining pack control and pulling away—so expecting to hit a home run ball by using the same old defensive strategy every time will only result more strikeouts.

Instead, teams need to play small ball, working to get the sure singles and doubles. Even if it means sacrificing a potential-but-risky grand slam opportunity, the team with lead jammer must know when to stop focusing on absolute jammer defense and start concentrating on trapping opposing blockers, so that they can best use their blocking resources to slow down the pack and bring home one or two “safe” points as the jammer comes home to score.

Mistake #1: Fraidy-Cat Call-Offs

Mistake #2 leads directly into the #1 mistake that players new to USARS roller derby make. And it’s a really, really big one.

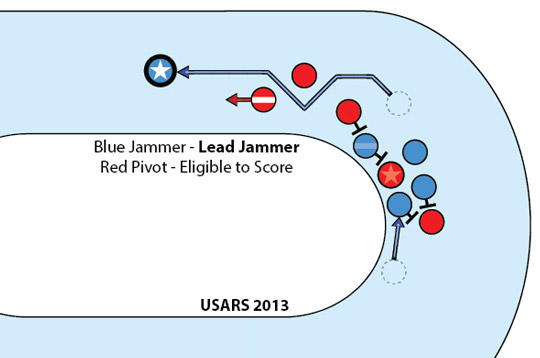

The lead jammer (or as USARS officially calls it, “lead active scorer”) has the power to call off the jam at any time. But this power can transfer to the opposing jammer (or pivot!) should they pass the leading jammer. Be they jammer or pivot, the lead scorer must always be the scorer in the lead, as USARS would say.

The bad news for USARS hopefuls: It seems as if a terrible habit has developed among the greater roller derby jammer population.

For some strange reason, jammers embattled in close jammer races default to calling off the jam before getting anywhere close to scoring position. It appears that they prefer taking a “safe” 0-0 jam outcome instead of doing their job—trying to score points—and having faith that their teammates will do their job and make some blocks to help them score—whether their team has lead status or not.

To put it bluntly: Jammers are ending jams far too early with pussy fraidy-cat call-offs, far, far too often.

You will see this a lot in USARS, especially in the early going of its roller derby program: The jammer breaks out of the pack, the pivot (or jammer) gives chase immediately, then the lead jammer calls off the jam for fear of getting passed, losing control of of the jam to the other team, and potentially letting them score points before they call it off themselves.

However, this “fear” of a jammer losing control is a misplaced one. Even with the ability to call it off—and the potential consequences of losing that ability—the lead jammer does not control the jam.

Yes, you read that correctly. The lead jammer position is overrated.

To prove the point, ask yourself: Why does a jammer call off a jam?

Have the opponents in pack clogged things up ahead of the lead jammer, preventing her from continuing forward safely? Is the lead jammer seeing that her teammates in the pack can’t effectively block the opposing jammer on her scoring pass? Did the team with lead jammer not keep containment on the opposing blockers, leading to a runaway pack situation?

In truth, the pack has more control over the termination of a jam than do the jammers. (With 80% of the players on the track, it bloody well should.) All the jammers are doing when choosing to call it off is reacting to what the pack is doing–or is often the case, not doing.

This is the biggest, most terrible mistake USARS jammers can make. On the verge of losing lead status in no-man’s land, a jammer desperate to put hands to hips without even considering what is happening in the pack is often throwing away a perfectly good scoring chance.

Favorable player personnel match-ups, relative pack position, penalty advantages, and the overall game situation should override any (false) fears of a jammer temporarily losing the ability to call off the jam. Because the jammer is not the one calling off the jam. In the end, it is the blockers in the pack that dictate when the jammer cries uncle.

Practically, if your blockers are doing a better job than the blockers on the other team, all calling it off early will achieve is to discard their hard work and waste the advantage they earned in the pack. Because at that point, who cares if the other jammer passes you? Let them decide if entering the pack first in an unfavorable scoring situation it worth it.

Deliberately allowing the opposing jammer/pivot to reach the rear of the pack first is a heavy concept, but stick with me. Here is an example to demonstrate why this is usually a good idea.

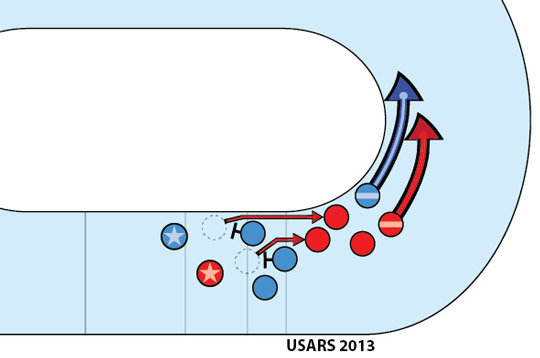

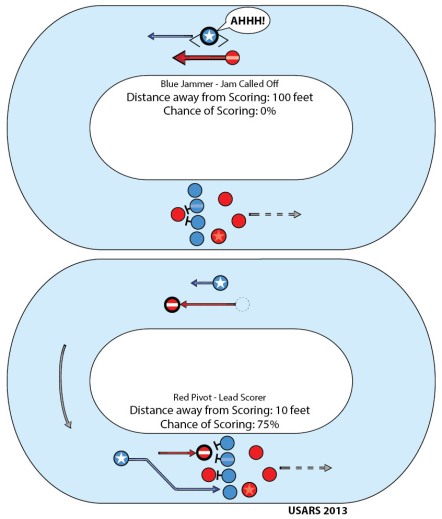

The blue team has managed to put together a 4-wall on a single opposing blocker, slowing the pack to a (rules-mandated counter-clockwise skating) crawl. This is their ticket to getting lead jammer, but it’s also a recipe for an immediate chase by the red pivot, seeing as she was left uncovered at the front.

The race is on. As it turns out, the red pivot is faster than the blue jammer, and will pass the lead jammer about halfway around the track.

A fraidy-cat jammer (AHHH!) would immediately end the jam to make sure the red team won’t score any points, at the cost of giving her team a 0% chance doing the same.

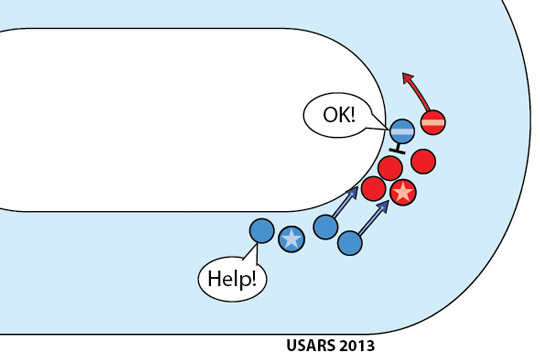

A real jammer—a team player—would be confident that her teammates could keep that 4-wall strong long enough for the opposing team’s scoring player to crash into it without scoring a point. This will allow the jammer time to regain any distance lost after getting passed for lead status along the way, which for a competently fast jammer should only take a moment, and generate a much more realistic scoring chance for her team than she would have got with a cowardly call-off.

Look at the second example above. Because the blue blockers are in perfect defensive position, the conundrum of when to call off the jam suddenly falls on the red team. Does she try to shove her way forward for a point? Does she risk squeezing to the outside, potentially losing the ability to call it off if she gets knocked out of bounds?

Should she just do the “safe” thing and end it 0-0 before the blue jammer sweeps around the red goat in the blue goat pen?

The idea behind the “always try to score” strategy is that teams will find more points if their jammers just put their heads down and get to the rear of the pack as quickly as possible, whether they lose lead status along the way or not. Assuming a jammer has decent blocking to back her up, it is infinitely more advantageous for her to be a fourth-whistle length away from scoring and have the other team end the jam 0-0; than to be half the track away from scoring and ending the jam 0-0 herself.

The closer you are to the business end of pack, the more likely you are to score due to mistake from the opposing team or a good play by your own teammates. The more you get into this position, the more points you will score in the long run. Ultimately, these fringe points can be the difference between winning or losing, especially in competitive USARS games where double-digit jam scores are unlikely and reaching 80 total points is merely extremely difficult.

Of course, there is risk in approaching the game like this. If your team is the one that makes a mistake or is the victim of a good blocking on the part of the other team, a play could backfire and you may lose more points on the jam than you could have potentially gained.

However, the great teams will understand this risk and learn to manage it and how to spread it out across different game situations within a single bout or an entire season. While individual jams (or even a whole game) may go badly, a better team will know that if it plays the percentages (and stays out of the penalty box) it will score more points than it gives up throughout a 60 minute game, win more games than it loses across a season, and ultimately have the knowledge and trust in one another to win a big game when it matters the most.

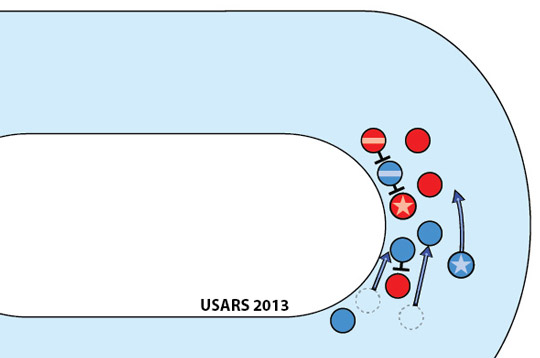

Consider if the above example happened multiple times throughout a game. Across four jams, let’s say. In a still-close jammer race, the red pivot (lead active scorer) will not have much time to work against the wall. Working off that, let’s assume he could manage to break through it (with one blocker to assist, the red goat) and call it off successfully 25% of the time. And just for the heck of it, let’s guess he picked up a loose point in one of the jams, too.

This means that in 4 jams where the red team had a scoring player enter the pack first, it picked up 5 points.

But think of what might happen in the other three jams, given the superior defensive position of the blue team in the pack.

In one, maybe the red pivot calls it off a hair too late and allows the blue jammer to steal the goat point before the fourth whistle. In another, maybe he does call it off too late after scoring on the loose brick in the blue wall, allowing the blue jammer to retake lead status, score on 3 red blockers, and call it off before the red pivot can do any real damage. And in yet another jam, maybe the blue wall escorts the red pivot out of bounds (preventing him from calling off the jam), giving the blue jammer plenty of time to pass back by the red scorer, take all 4 points in the pack and then call it off—or maybe, trust his blockers to make a go at another scoring pass.

So while the red team may have gotten through the wall once in four jams and picked up 5 points, over the course of several jams it is totally feasible that, with total pack control and solid defense during the scoring pass, the blue team will have picked up 8 points or more.

Had the blue jammer chickened out and called off those four jams without ever attempting a scoring run, the blue team would have scored zero points.

Which score differential would you rather have: 8-5, or 0-0?

This is the mistake that teams new to USARS are making when they call off the jam too early. It is a twofold mistake, actually: Jammers afraid to begin a scoring pass as second banana are too worried about what points they might lose in the immediate future, rather than thinking about the points their team may gain in the long run. And jammers that do not practice taking a tardy plunge will not give their team enough data or experience to make better risk management decisions in all game situations, not just the safe and easy ones.

If USARS teams stipulate—for training and scrimmaging purposes only—that jammers (or pivots) are forbidden to call off the jam until someone has scored a point, they will be shocked at how often they can score in seemingly unlikely scoring situations. It will also teach teams how to best position themselves on defense for the scoring pass, and how their actions during the initial pass can help or hurt them in that regard. (See: Mistake #2 and Mistake #3.)

Best of all, it will train jammers to trust their blockers on a scoring pass, teach blockers how to block better as individuals and a group, and make a team believe can score in any situation if it has the faith and ability to pull it off.

Unless, of course, the team is afraid of making mistakes.