Roller Derby’s “Default” Level of Difficulty

As shown using 2013 game data and the PPJ metric, roller derby rules have a significant impact on how competitive roller derby jams can be. Now it is time to demonstrate which rules have this impact and why some forms of roller derby can be more competitive, across all skill levels, than others.

Everyone has long since updated their rule books for the 2014 season, so from this point forward we will be talking about things from the perspective of this year.

Still, enough similarity still exists between 2013 roller derby and 2014 roller derby that we can the 2013 PPJ data to help make further observations about competing for points in each game environment.

There are no significant differences among the gameplay philosophies of each of the four derby organizations, when compared to last year. Certain “core” rules have the greatest effect on scoring difficulty and overall game competitiveness, and no organization did anything to alter their respective cores.

In fact, multiple derby variants share many of these core rules, even if they are implemented or applied differently. These are the ones that help shape competition, since they are interconnected and rely on each other to work optimally.

Here are those among the most prominent in assuring jams, and games by extension, are as fairly contested as possible.

– – – – – – – – – –

“Team” Defense and Pack Definition

If one team is doing a very good job on defense in the pack, that should consistently give them a good chance of succeeding on offense. That’s Roller Derby 101.

Now for Roller Derby 102: What does it really mean to play defense in a team sport?

In modern roller derby, as it currently exists, there are two different philosophies on the meaning of “defense.”

In the WFTDA, playing defense means “stop the jammer.” In its rule set, a team need only defend one player, the opposing jammer. Depending on how well it does this, it can deny the opposition a chance to work together as a team, giving them no way to counter offensively and quickly complete their initial pass. Let alone, score any points on the play.

In the RDCL, MADE, and USARS, playing defense means “stop the team.” In these rule sets, a team must not only defend the opposing jammer, but must simultaneously contain at least one other opponent to ensure a good offensive opportunity. In being made to do so, however, the opposition is allowed ways to work together on offense, ultimately giving them a proper chance of scoring points—or at least, a real chance of preventing them.

Put another way, no matter how one team plays defense together, the other team will always have a chance to play offense together. When a competent team always has a chance to play offense together whenever it wants, it will always have a chance to compete for points.

This is in major part due to pack definition and its related rules, which helps to make sure uncontested points in the RDCL, MADE, and USARS are hard to come by and keeps PPJ averages low, no matter who is playing against who.

Teams are afforded at least two ways to play offense during regular jams, as commanded through game rules, so defenses need to cover them all to gain a superior defensive position. By itself, this is not too difficult for a good team to do.

The tricky bit is keeping such an absolute defense going while simultaneously keeping the pack slow. Slowing down the pack will allow a jammer to more easily come around and get into scoring position, but this simultaneously gives more opportunity to the opposition to free their jammer offensively.

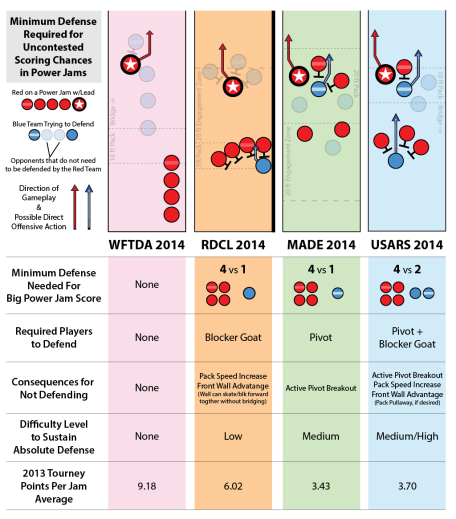

Which is what the blue team is trying to do in the chart below. Here, the red team is in good position for lead jammer and to maintain a slow pack.

Take note of who the red team needs to cover (solid blue players) and who it can generally ignore (faded blue players) on defense in each of the four rule sets, and how difficult it would be to keep the pack under their control as a result.

Then compare that to their respective PPJ averages from 2013. You should see a connection between how much opportunity the blue team has to work together offensively (the blue arrows) and how many jams are equally contested across games of all skill levels.

This concept is easier to understand if you look at examples in gameplay environments outside of the WFTDA derby we all know. Like it, RDCL play requires both jammers to clear an initial pass for their teams to be eligible to score, which is good for a parallel comparison.

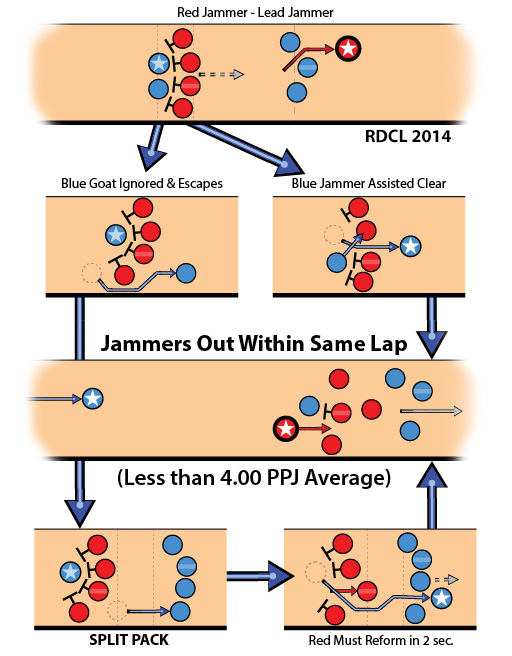

The rear 4-on-1 blockers-on-jammer wall is an extremely common play in the WFTDA. It also happens in the RDCL, but not nearly as frequently, or for as long, or as effectively. For good reason.

RDCL rules feature no destruction of pack penalties, no immediate failure to reform penalties, and a persistently defined engagement zone during split packs. As a consequence, should the red team allow the blue team to all get to the front of the pack, the blue team may legally destroy it to temporarily increase its speed and stay together in a wall without necessarily having to bridge back.

The blue team can control the speed of the pack and remain in a 4-wall formation indefinitely from this position, so long as it pauses acceleration to allow the red 4-wall to catch up and reform the pack.1 But once the pack snaps back together, the blue team can legally split it again and speed it forward.

This repeating cycle of speed-slow-speed-slow will always favor the team wishing to do the speeding, the blue team in this example. This is sub-optimal for the red team, who with lead jammer would wish to do the slowing and keep it slow for a potentially big score.

For the red team to have its wish granted, it would need to keep at least one blue blocker behind them defensively at all times. Doing this affords the red team the privilege of pack speed control, as well as the getting to watch the remaining forward blue blockers get pushed 20 feet forward out of play by the red jammer.

With good defense against the jammer and a blocker, the red team is in a good offensive position to score points. At the same time, however, this necessarily puts the blue team in an equivalently fair offensive position.

Once the red jammer gets clear for lead, the blue team will have a 5-on-4 pack advantage, no different than if they were on a miniature power jam. The blue team can use this extra body to work together, overpower the red defense, and break the blue jammer out of the pack relatively quickly.

Unless the red defense is significantly better than the offense it is trying to contain, this is a battle that will inevitably fall in favor of the blue team on every jam—one way or the other.

If the red team lets the goated blue blocker go to focus only on the blue jammer, it will give pack advantage to the blue team in the process. From the front, the blue team can strategically and legally increase speed and split the pack to directly help their jammer.

Splitting the pack forces the red team to break up its defensive wall to reform the pack from behind. But in doing so, it must simultaneously look back to block the blue jammer. The rear wall will eventually become disjointed while having to concern itself with two conflicting responsibilities, creating a gap and exit lane for the jammer.

For the red team to avoid this from happening, it will want to keep hold of a goat. However, a goat trapped behind a 4-wall with a jammer is also an offensive assist for a jammer to help get through that same 4-wall.

It doesn’t matter if the blue team is in front of their opponents or behind them: Because it has offensive options no matter where it is situated in the pack, it will always be able to use teamwork to have a chance to play offense. It’s up to the red team to work hard on defense to stop those chances if it wants to do well.

Yet even if the blue team isn’t good enough to actually break their jammer out, their offensive efforts should at the minimum force the red team to skate forward at some speed to keep up their containment, forcing the red jammer to have longer loop-arounds on scoring passes.2

If even a bad team can create a rolling pack, extreme jam scores become rare, and jams overall become much more competitive across all games played. This helps explain the 6.02 PPJ average calculated for RDCL games played last year.

Contrast this with the WFTDA and its 2013 tournament scoring rate of 9.18 PPJ. In the WFTDA there are many situations where even the best teams have no way of offensively helping their jammer, either through blocking or pack speed control, if she gets gunked behind a rear wall and recycled.

In fact, any offensive attempt by teammates to help a recycled jammer by skating back to her will move the pack back with them. If they could somehow get there to engage, they would be unable to legally throw positional blocks while stopped or in the clockwise direction. This means trying to work together offensively makes their situation even worse!

How can roller derby truly be competitive if all five members of a team don’t always have a fair opportunity to play offense together, no matter the level of their skating skill?

If WFTDA blockers trapped at the front of the pack had a second option on offense besides the “pray your jammer doesn’t get recycled or get a penalty” strategy, all players on a team would always have a way to directly contribute on offense. This is because their opponents would be forced to account for what they can do to help their jammer, no matter where they are on the track.

This is how pack definition rules make sure jams are more competitive for everyone, both offensively and defensively. With a “default” chance for blockers to define the pack in their favor, even an outmatched team can take advantage of the defensive failures of an opponent.

Even when that defense has no jammer to defend.

– – – – – – – – – –

Power Jams, Penalties, and Pack Control

Here is the interesting thing about roller derby power jams, as most know them: Technically, they are not roller derby.

Roller derby is a game where both teams play offense and defense simultaneously. If one team has no opportunity to play offense, and the other team sees no need to play defense, both teams are not playing offense and defense at the same time. By the textbook definition, a power jam of this manner cannot be roller derby.

Yet there are ways to adhere to the proper definition during the situations where there is only one jammer on the track at any given moment. Doing this keeps regular jam scoring balanced with penalty-heavy scoring in such a way where the value of an individual point, and the effort necessary to earn it, is the same either way.

Basically, rules must force a team to play defense throughout an entire jam, lest they face consequences. Including while on a power jam. This makes sure there are consistent consequences for bad teamwork or individual mistakes, allowing their opponent to take the advantage and have a chance to counter offensively on the penalty kill.

Yes, offensively. Offense with your jammer in the penalty box.

In this next diagram, we will remove the blue jammer and see what happens from the perspective of the red team, who has lead jammer and is about to complete a scoring pass. We know the blue team can’t get lead jammer and/or score points; that’s the consequence of its mistake, the jammer penalty. We know who the blue team is trying to defend against.

We also know what the red team is trying to do on offense. But for it to really be roller derby, it also needs to be playing defense simultaneously. Who does the red team need to play defense against? And if the red team makes a defensive mistake on the power jam, what consequences does it face as a result?

Here we can see how pack definition plays a major part in ensuring that both teams have an appropriately fair chance to play offense and defense on power jams. We once again look to the RDCL scenario for the best example of this.

With the blue jammer in the penalty box, the red team enjoys a big advantage. As it should. But this advantage does not grant the red team immunity from punishment for bad defense or committing penalties. Like any advantage, it can be squandered with mistakes such as poor blocking or penalties.

The red team can only cash in big on its offensive chance if it simultaneously plays a basic amount of defense, in this case containing a single blue blocker. Doing so prevents the blue team from speeding up the pack or creating a strong forward rolling 4-wall, as explained before.

To do well on offense, the red team must do well on defense simultaneously. That’s roller derby, even during power jams.

If it can’t do well on defense and the blue team offensively frees their goat, on the other hand, the red team can forget about a big power jam score.

That’s right: Offensively. The blue goat can be freed as if she was a jammer offensively breaking through the opposing defense. Even if that blocker is not eligible to come around and score points, the mechanics of her getting through the red team and gaining advantageous forward position is exactly the same.

So it is also with blocker penalties. If red blockers start riding the pine, holding back the “offense” of the blue team with fewer defenders becomes much more difficult to do—let alone doing it while keeping the pack slow.

Unless the players in a red micro-pack are significantly better than the other blockers on the track, a faster pack is likely to happen as the blue team together constantly attacks the red defense. This naturally leads to longer jammer scoring laps and a lower power jam score.

By way of defensive miscues or blocker penalties, the red team gets punished for their mistakes to the tune of diminishing their chances of scoring well on offense. Power jam or not.

Contrast this with how power jams often go in the WFTDA, where there are few or no consequences for blocker penalties or (defensive) laziness. Teams that activate offensively at the right time can be rewarded by forcing an pack split/bridging situation, yes. Yet, this strategy requires no simultaneous and persistent defense to gain access to.

To do well on offense, the red team need not play defense simultaneously. By any definition, that cannot be roller derby.

Power jams like these throw gameplay out of balance, even in games between highly-skilled teams. This factor helps to further explain the much, much higher PPJ average across all of WFTDA roller derby last year.

This, despite the fact that both the RDCL and WFTDA had 60-second power jams last year—a duration that is not changing in the RDCL any time soon.3 Why would it need to, when the scoring effects of RDCL power jams remained much more in balance with regular jams due to its rules differences?

In the RDCL (and USARS, too) the team that best holds control over the blockers on the other team defensively is the team that earns the best chance of success on the power jam offensively. During power jams or during regular jams, the conditions for success, or failure, are the same for both teams.

If teams are not able to directly compete against each other for points due to jammer penalties, rules should make they sure have the same opportunity to compete for the next best thing: Pack speed control, the major factor how successful a team is at scoring offense (slow pack) and scoring defense (fast pack).

– – – – – – – – – –

Active Pivots and Fair & Equal Jam Starts

In the WFTDA and RDCL, a jammer must physically pass their helmet cover to the pivot in order to transfer points-scoring abilities on the jam. In MADE and USARS rules, pivots can break away from the pack to become a jammer without a star pass, but only after an opposing team has made their way through the pack on the initial pass to pick up lead.

The role of the pivot is the single biggest difference between the two styles of roller derby. It is also the single biggest reason why the average scoring rate in USARS and MADE is below 4.00 PPJ—and the numbers in the RDCL and WFTDA are some distance above it.

With a front-loaded active pivot, it is extremely likely that both teams will have someone jamming on the same scoring lap, making jams ideally competitive almost every time up.

Hold on: Wouldn’t giving a team the ability to send away their pivot from the front of the pack make it easier for it to score? The claim is a lower PPJ should make it more difficult to put points on the scoreboard. Without ever needing to get their jammer out of the pack, the implication is that a pivot break will ensure a team an easy chance to get points every time.

That teams may appear to have an “easy” way to get a scoring chance on every jam is completely irrelevant. In reality, the only thing that matters here is that both teams start with an equal opportunity to get a scoring chance on every jam. This is because both teams start a jam with the exact same legitimate offensive threat available to them to initiate that scoring chance.

By default, this offensive threat is not the jammer.

It’s actually the pivot.

In MADE and USARS, pivots (and jammers) are required to start every jam and pivots must start at the front of the pack. These requirements hold even if the player wearing the star or stripe is seated in the penalty box at the end of the previous jam; they remove their cover and finish their penalty as a blocker into the next jam.

When both teams are rule-bound to field a pivot on every jam, both teams have the same chance to break a player away from front of the pack. Neither team starts with an advantage or disadvantage here, because both teams begin a jam in equal position to lap4 opponents—from ahead of everyone else.

Yet in spite of their scoring abilities, pivots can never be the first player out of the pack to start a scoring pass. (That would be far too easy.) This being a competition, teams are made to compete against each other for the strategical advantage of breaking away from the pack first and with as much of a head start as possible.

We better know this advantage as lead jammer.

The team—not just an individual on it—that plays effective offense during the initial pass while simultaneously playing effective defense to hold back the other team—not just an individual on it—will emerge with lead and have the advantage going into the pack on the scoring pass. The bigger the desired advantage, the harder they will have to work for it on offense (slow pack) and defense (containment).

Getting positioning advantage during the initial pass is critical. From an advantageous pack position, a team can more easily defend an opponent at a speed that allows for good scoring opportunities.

Every rule set has a naturally advantageous position within the pack as a consequence of pack definition rules, an advantage that is often exploited by a team whenever the opportunity presents itself.

But even here, rules must be in effect to ensure teams have an equal opportunity to compete for what they want, even before the very first whistle.

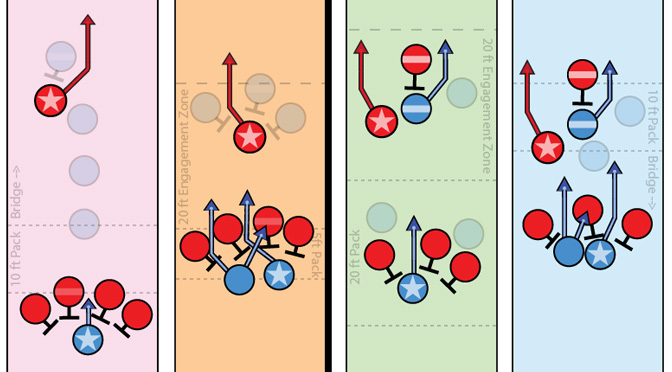

In our next diagram, note how the rules force certain players (circled in yellow) to line up in certain positions at the start of a jam. It’s here where we see another spooky commonality.

Unlike the points per jam tables on the previous page that showed very similar figures across multiple WFTDA events, below we see very similar jam start formation rules across three of the four gameplay environments.

If the red team wants to gain a comfortable defensive position after a jam starts, how is it made to fight against the blue team to earn it? Given how the pivots, blockers, and jammers line up, how hard must the red team work to do what they want offensively, without spoiling what they want to do defensively?

The start rules in the RDCL, MADE, and USARS are eerily similar—RDCL and USARS, virtually identical—despite all three of the organizations promoting different styles of play and developing their rules independently of each other.

All three of them require both teams to field a pivot and place them on the pivot line. All three of them also forbid the formation of a 4-wall before the jam starts, forcing blockers to directly compete with one another for positioning after the whistle.

And all three of them had significantly more competitive jams in 2013 compared to that of the fourth—the WFTDA, which just so happens to have none of these requirements during jam starts.

Are these similarities just a coincidence? Or is there something bigger at work here?

Making pivots just as important as jammers, as in MADE and USARS, is the cut-and-dried rules can guarantee good competition. But even without them, equal jam starts and pack definition rules, as seen in the RDCL, and act as a good compromise on competition and keeps jam scores competitive.

Without either, however, a butterfly effect occurs.

Good teams can often overcome the starting disadvantages they may be forced into. But even slight mismatches can often cascade into large jam score wins, for the simple reason that an inferior team has no way to help their jammer defeat a team starting in a superior defensive position, a position they did nary a thing to earn.

When teams are made to compete for position at the start of a jam, the team that winds up getting the positioning they want did so because they worked harder than their opponent, on both offense and defense.

A team that earns this positioning can then use it to help compete for lead jammer during the initial pass. The team that gets it did so because they worked harder than their opponent, on both offense and defense.

The team that earns lead jammer will have an advantage as the players in the pack begin to compete for points on the scoring pass. The one that works harder than their opponent, on both offense and defense—and without making any mistakes—will be the one that score positive points on the jam.

In a highly competitive roller derby game environment, particularly if an active pivot is in play, that score will typically be no more than four points. Four hard-earned points by a team five roller derby skaters. Contested in every single moment, of every single jam, in every single game.

Rules ensure this competition, because rules make doing things the easy way, the unsuccessful way. In a competitive environment, the only way to score points is to work hard; the only way to score more points is to work harder.

That is the true difficulty of roller derby, and indeed in all of sports.